Meat has become a scapegoat for so many of the world’s problems, blamed for everything from cancer to climate change. Is eating meat the problem, or is it the way we source our meat that’s really to blame? What if we shifted our appetite from intensively farmed livestock to eating the real problem – the millions of pest animals destroying the environment? Could hunting and eating wild game be the solution?

Demonising meat

Over the last decade, we have been told that consuming meat causes cancer, diabetes, heart disease, obesity, erectile dysfunction, acne, Alzheimer’s, a shorter life span and a number of other chronic illnesses, and that farming livestock is the leading cause of climate change, carbon emissions, acid rain, soil erosion, deforestation and a dozen other environmental disasters.

Why this push to demonise meat? What is the real agenda? And how many of these claims are backed by real science?

Why this push to demonise meat? What is the real agenda? And how many of these claims are backed by real science?

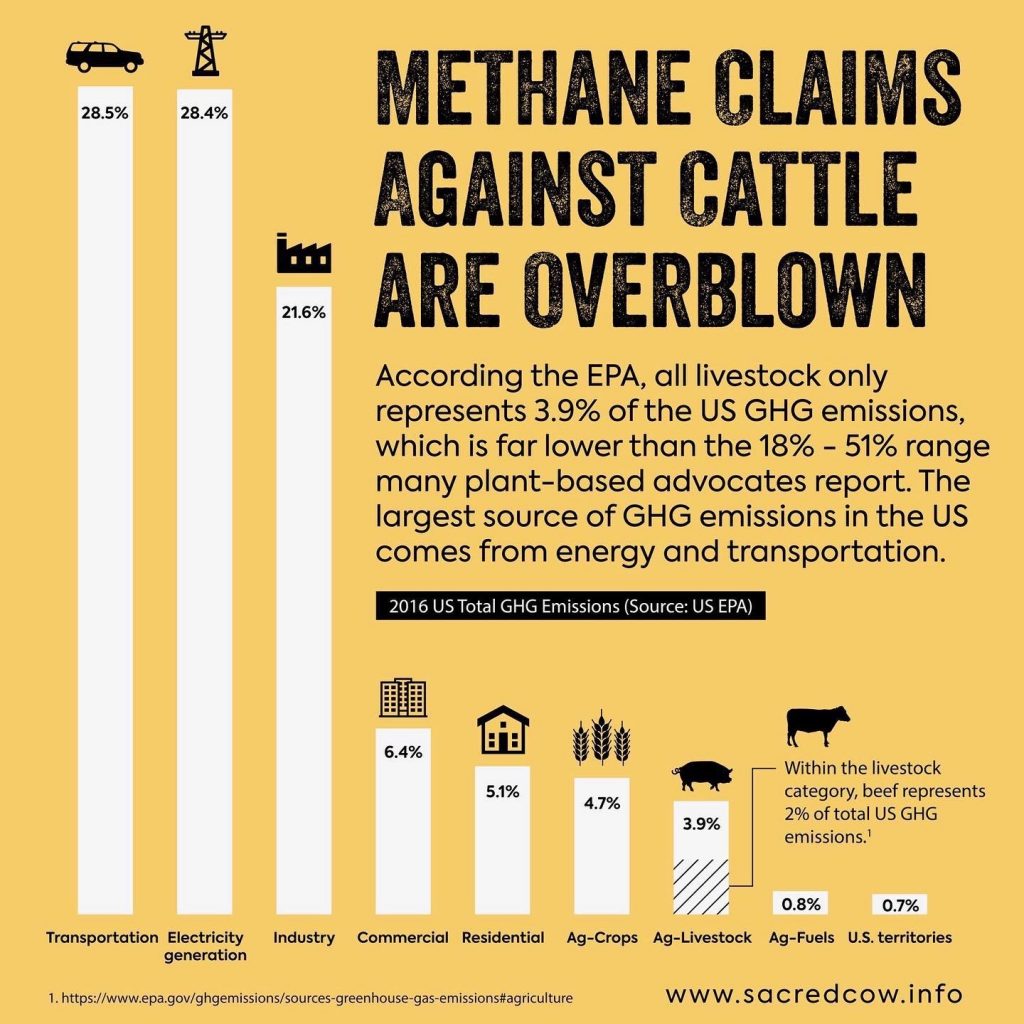

In April 2017, The Conversation published an article that blamed meat for everything from environmental damage to hurting the poor, to making us sick and causing harm to animals. The journalist quoted that livestock generates 18 percent of greenhouse emissions in the US and said this was more than all transport sources put together.

Turns out those figures were a lie.

A little over a year later, the same publication published another article setting the record straight. In October 2018, The Conversation published that transport accounts for around 28 percent of greenhouse emissions in the US, while livestock is only 3.9 percent.

Unfortunately, once these claims are made, they are very hard to wind back. Humans tend to believe what they hear first, and rarely check the facts for themselves. In other words, once you ring a bell, it’s hard to unring it.

This is why activist groups tend to make such provocative statements. It really doesn’t matter whether it is true, partly true or totally disproven at a later stage – there will always be a percentage of the people who saw that statement who believe it is Gospel!

Science vs fiction

Humans have been eating and farming meat since the dawn of time. So how has such an ancient food source become the scapegoat for some many modern diseases and problems?

Whether you believe in evolution or creation, both science and religion place a strong emphasis on meat being a major factor in the advancement of human civilisation.

Paleoanthropologists believe humans have been hunting and eating animals for more than 3 million years, and attribute cooking and eating meat as the driving force for making us human, for developing our large brains, and catapulting us to the top of the food chain.

In Genesis 3:21, God killed the first animal, clothing Adam and Eve in its skin. In Genesis 9:3, God tells Noah that everything that lives and moves about has been given as food for humans.

Archaeological evidence shows humans began domesticating animals for food around 10,000 BC.

All meat diets

While there are organisations that would have you believe the whole world should go meatless for our health and the environment, there are many areas around the world where the landscape cannot support large scale agriculture. As a result, the tribes who live in these areas survive almost entirely on animal products.

Take the nomadic Maasai tribes in Tanzania. They have baffled scientists for years. Despite surviving on a diet of raw beef, cow’s blood and cow’s milk – foods we are led to believe cause heart disease – the Maasai have great heart health.

The Inuit tribes in the frozen Polar regions eat only what they can hunt, fish or forage. They eat moose, caribou, polar bear, ducks, geese, ptarmigan and fish. But the bulk of their calorie intake comes from whales, seals and walruses, due to their high fat content. Even with a diet high in animal fats, the Inuit people have better health outcomes than most Westerners.

There are many other tribes just like them that show meat has never truly been the problem. The real problem lies in our increasing urbanisation, our addiction to consumerism and the way we source foods.

Modern life, modern foods, modern problems

Since the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s, the global population has increased from 679 million to 7.53 billion while also transitioning from rural communities to large urban centres.

Today, around 55 percent of the population (or 4.14 billion people) live in cities and urban areas, and are completely reliant on a global supply chain made up of large-scale famers, food production companies, and supermarkets to feed them.

Ironically, the more removed the population has become from the source of the food, the more critical and vocal they have become about how food is farmed.

The paradox of the current anti-meat agenda is that plant-based diets are hard to source locally. They rely heavily on mass-produced meat-alternatives and imported fruits, vegetables, grains and oils. These foods are often monocultures, grown under intensive agricultural practices that have a negative impact on the environment.

Take soy beans as an example – a key ingredient in most manufactured foods. Soy crops are a major contributor to deforestation, which removes the habitat of many threatened tropical species. There are many people who will tell you the majority of soy beans go to animal feed. While this is technically true, it is a gross misrepresentation of the facts.

Soy beans are grown primarily for their oil, which is extracted and used in foods (68%), bio-fuels and bio-heat (25%) and industrial products such as paint, plastics and cleaners (7%). But the oil only accounts for 20% of the actual bean. The other 80% of the bean is silage – or waste product. This is ground down to make soybean meal. Now 97% of this meal gets fed to livestock, while the remaining 3% goes into meat alternative products and soy milks.

See what happened there? By twisting these figures, activists would have you believe soy bean farmers primarily grow their beans to feed to factory farmed livestock and therefore, farming livestock is what really causes deforestation. In actual fact, human consumption is the primary purpose for growing soy beans and generates the vast majority of the income. A ton of soy bean oil sells for $560 while a ton of soy bean meal sells for $286.

The meal is essentially a waste product. Farmers have found a way to supplement their income by finding an alternative use for what they otherwise would have paid to dispose of.

Activist groups have been twisting facts for years to push their meatless agenda, which has led to many people believing the choice between meat or plant-based diets is a choice between two intensive farming practices, and that the ethical choice is choosing the lesser of two evils.

But what if the real solution doesn’t involve giving up meat or choosing a highly processed meat-alternative? What if we just need to think outside the box?

Eating the problem

Did you know: the vast majority of the foods we eat in Australia – both meat and plant based – were introduced from another country.

Since Australia was settled in 1770, over 3000 animal species and 27,500 plant species have been introduced to the country! Most of these remain domesticated and under control. However, there’s a growing number of species that are now considered invasive. Invasive is a classification that means they have a negative impact on the environment, our economy or human health.

When it comes to invasive species, the first ones that generally spring to mind are rabbits (10 billion) and cane toads (200 million), which are in plague proportions around Australia. But there’s some other heavy hitters in the animal kingdom including:

When it comes to invasive species, the first ones that generally spring to mind are rabbits (10 billion) and cane toads (200 million), which are in plague proportions around Australia. But there’s some other heavy hitters in the animal kingdom including:

- Feral pigs (24 million)

- Foxes (around 7.5 million)

- Feral cats (around 6 million)

- Feral donkeys (around 5 million)

- Feral goats (2.6 million)

- Feral camels (1.2 million)

- Feral horses (400,000)

- Water buffalo and feral cows (200,000)

Deer are another species that are generally considered invasive due to the large number of them (there’s no definitive number but estimates are in the millions), but that largely depends on where you are in Australia. In Queensland, Northern Territory, South Australia and Western Australia, deer are considered a pest species. In NSW, Victoria, and Tasmania, they are considered game animals and often protected. Some have even erroneously classed them as feral, but the true definition of feral is a species that was once primarily domesticated that is now wild. Deer have never really been domesticated except in small numbers. They were introduced as wild game animals. But regardless of whether we classify them as pest, feral, invasive or game, deer populations do need to be managed.

Deer are another species that are generally considered invasive due to the large number of them (there’s no definitive number but estimates are in the millions), but that largely depends on where you are in Australia. In Queensland, Northern Territory, South Australia and Western Australia, deer are considered a pest species. In NSW, Victoria, and Tasmania, they are considered game animals and often protected. Some have even erroneously classed them as feral, but the true definition of feral is a species that was once primarily domesticated that is now wild. Deer have never really been domesticated except in small numbers. They were introduced as wild game animals. But regardless of whether we classify them as pest, feral, invasive or game, deer populations do need to be managed.

We also have billions (yes, with a b) of rodents, insects, birds, fish and invertebrate species that are considered invasive pests.

Invasive pests are not just introduced. Native species such as kangaroos, wallabies, possums, cockatoos, ducks, swans, kookaburras, crows and many others can also be considered pests when their numbers get too high, or they have been introduced to new areas.

Invasive pests are not just introduced. Native species such as kangaroos, wallabies, possums, cockatoos, ducks, swans, kookaburras, crows and many others can also be considered pests when their numbers get too high, or they have been introduced to new areas.

The combined cost of managing invasive species in Australia is around $13.6 billion a year – a cost largely borne by taxpayers or passed on to consumers.

So how are pest species managed?

The most common control methods are trapping, fencing, poisoning, biological diseases, and/or shooting. The government also use some non-lethal methods (sterilisation and relocation) but these are expensive and have proven to be ineffective in dealing with the widespread problems we have with invasive species in Australia.

The most successful methods are nearly always lethal.

Did you know that the government culls more than 3 million kangaroos and wallabies each year, with millions more shot by hunters and farmers around the country?

All of these deaths are necessary to ensure food supplies are secure, that our environment is protected, and that we keep our country free of disease. But most people who live in the cities have little to no idea that these deaths occur – sometimes right under their noses (have a quick look at the pest management programs run by your local council).

Unfortunately, the vast majority of the animals killed as part of these programs go to waste. Even hunters only eat a small portion of what they kill.

When it comes to meat, Australians consume an average of 125kgs per person per year – or around 350g a day. Australians prefer the commercially farmed varieties we find in the supermarket: beef, lamb, pork, and chicken. We eat a little bit of seafood and might dabble in a couple of game varieties such as venison or duck, but eat very little native or wild game meats.

But unlike plants – the majority of which are toxic or inedible – almost all animals can be eaten.

MONA Museum in Tasmania had an Eat the Problem exhibit a few years ago that looked at turning feral cat, cane toad and fox into haute cuisine dishes. While I am not sure those particular pest species will gain mainstream traction as table fare, Australia does have a bounty of wild, organic, free-range meats available for those willing to stretch their culinary horizons. Rabbits, feral pigs, donkeys, goats, camels, buffalo, scrub bull, duck, pheasant, deer, trout, carp, redfin perch, bream, tilapia, and even kangaroos and wallabies are all edible meats. If you want to get adventurous, Australia has a plethora of wild birds that can also be eaten: swan, cockatoo, crow (remember the song about 4 and 20 blackbirds baked in a pie), pigeon, bush chooks, quail, guinea fowl, turkey, doves…

The good news – for the most part, all of these meats are free and plentiful if you hunt or fish them yourself.

If we shifted our appetite away from intensively farmed livestock to eating the real problem, we would go a long way to managing our wildlife problems and, in the process, reduce the impact intensive farming has on the environment.

Forget Meatless Monday. Marine Monday, Wild Game Wednesday and Feral Friday will still reduce our reliance on intensive farming, and has the added benefit of helping solve a much bigger problem with invasive, feral and pest species.

Are you game to stretch your meat options?

What is I Am Hunter?

I Am Hunter wants to change the way hunting is perceived and to change the conversation from a negative one driven by anti-hunters to a positive one led by hunters.

Our goal is to help hunters become positive role models and ambassadors for hunting, while simultaneously helping non-hunters understand why hunting is important.

You can become a supporter and help us achieve our goal and spread a positive message about hunting with the wider community.

Our other channels

Get our newsletter

Get our free monthly newsletter direct to your inbox

Listen on iTunes

Listen to our podcast on iTunes.

TV series

Watch I Am Hunter episodes on My Outdoor TV (MOTV)