There’s no denying zebra are iconic to the African continent. It’s hard to think about Africa without imagining a herd of black and white striped zebra grazing across the open plains. Maybe that’s why some find it so hard to understand how someone could kill one or why anyone would hunt a zebra. In this article, we’ll explore some of the common questions and objections people have about hunting zebra and look at how hunting and conservation often go hand-in-hand.

Reading between the lines

Zebra might not be the most famous African animal, but they are certainly a worthy supporting cast member. The humble zebra is a regular feature on postcards and travel brochures. It has also featured in almost every documentary, movie or kid’s cartoon set in Africa.

Its distinctive black and white stripes stand out while simultaneously helping it blend into the background. They are also unique, as in no two zebras have the same stripes – much like a human fingerprint.

Zebras are a majestic animal that can evoke strong feelings in people. Feelings of love towards the species itself, and anger or disgust towards anyone who tries to harm them.

Perhaps that’s why they are such a controversial species to hunt, and why hunting zebra can cause bitter disagreements even amongst other hunters.

There are a few reasons we feel such a strong affinity with the zebra.

For starters, they bear a close resemblance to the domestic horse, and because horses have played such a strong part in human civilisation, it’s almost impossible not to have some emotional attachment to them. Maybe you grew up riding them, or dreaming of riding them, or just admiring them from a safe distance.

This is perhaps why even hunters feel conflicted at the thought of hunting zebra. It’s the same conflict some of us feel when hunting feral cats and dogs – it’s hard to separate the wild animal from the domesticated one we may have a strong emotional attachment to.

I know I felt this conflict the very first time I tasted zebra meat. I enjoyed the taste, but having grown up as an equestrian, I felt almost a deep sense of shame and guilt at eating a horse cousin!

Disney has also done a great job of anthropomorphising animals. We grew up watching movies and cartoons where animals were given human names and traits and family structures.

Who doesn’t look at a zebra and almost imagine it with Chris Rock’s voice?

Yet, as familiar as they are, they are also exotic, and we tend to want to protect that which we presume is rare and beautiful.

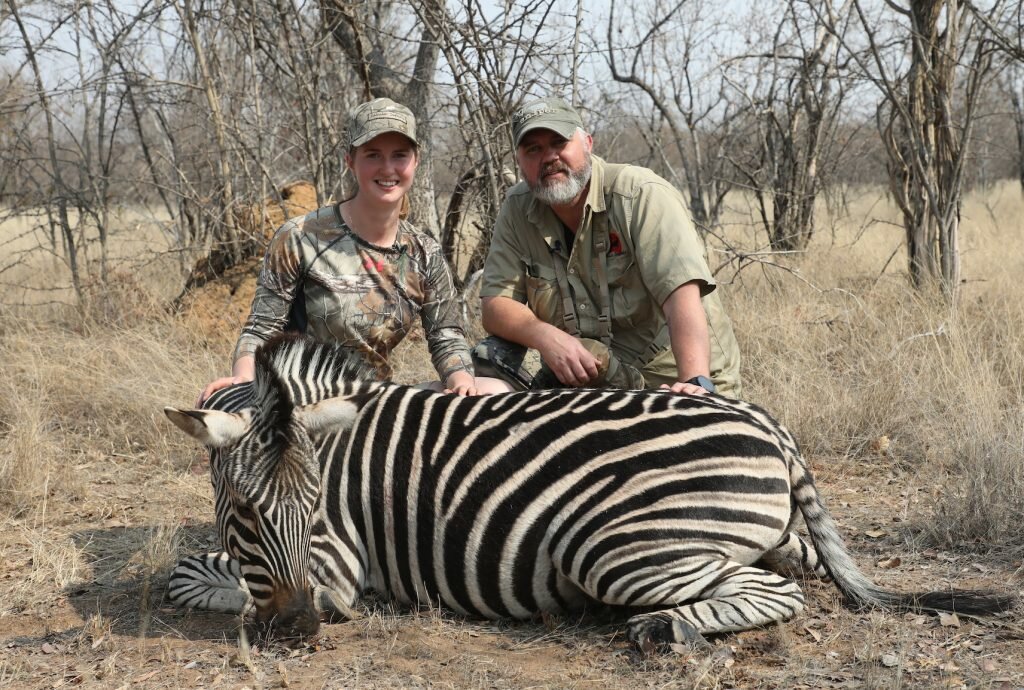

When Jess hunted a zebra in episode 8 of I Am Hunter, she correctly surmised that most of the angst people feel about hunting zebra has very little to do with rationale and facts, and is almost purely an emotional response.

But isn’t that the way with most hunting?

Let’s examine some of the common questions people have about hunting zebra, dispel a few myths and hopefully help you gain a better understanding of how conservation and hunting go hand-in-hand in protecting zebra and other iconic wildlife.

Are zebra endangered?

When it comes to conservation status, the answer is rarely black and white (pun intended).

For starters, zebra is the common genus. There are actually three sub-species of African zebra and their individual conservation status depends on many varying factors.

While it’s important to factor in the overall conservation status of the species as a whole, it is perhaps even more important to consider their status in the country you are visiting, as the situation may differ greatly from location to location.

This will also impact whether they are hunted locally or not.

So let’s take a closer look at the three sub-species of zebra:

- Grevy’s zebra (equus grevyi) are the largest of the three sub-species, as well as the largest living wild equid (horse-like species). You’ll notice the stripes are also thinner, and almost create a dizzying and hypnotic geometric pattern. The Grevys are found only in Ethiopia and Kenya, and with less than 3000 still remaining in the wild, they are the most endangered of the three species. Despite its endangered status, the population is considered relatively stable, which means it is neither increasing nor decreasing.

- Mountain zebra (equus zebra) are native to the hot, arid regions of South Western Africa, namely Angola, Namibia and pockets of South Africa. It is the smallest of the three species, has a white belly, and narrower hooves than its cousins. Its ear are more prominent, and it also has a slight dewlap on its throat. With an overall population of between 50,000 and 100,000, the IUCN considers the mountain zebra to still be vulnerable, despite the fact that its population has been steadily growing for the last few decades (up from a low of around 80 in the 1950s to today’s numbers). Namibia has the highest numbers followed by South Africa and then Angola.

- Plains zebra (equus quagga) are both the most populous (around 500,000 exist in the wild) and the most commonly seen zebra, though technically, there are 7 sub-species even of the plains zebra. For simplicity, we want go into each of them, but look at the plains zebra as a whole. They have wider stripes that can either be black, brown or a combination of the two. They are also the most geographically spread out, occurring in 17 of the 54 African nations. While they are stable or increasing in 7 countries, they are decreasing in the other 10, which gives them an overall category of near threatened. However, if you break it down by country, they are actually considered of least concern in South Africa, which has one of the healthiest populations (probably due to its private ownership laws). When zebra are hunted in Africa, 9 times out of 10, it will be a Plains Zebra that is being hunted and most likely in a country where their populations are considered healthy.

There’s a photo on Wikipedia that shows the species side by side, which may help show the subtle differences between each species.

If plains zebra are near threatened, why are people still hunting them?

This is where things get a little complicated, as your thoughts around hunting may be highly dependent on where you grew up.

Here in Australia, the vast majority of hunting centres around population control. Almost all of the species that we hunt were brought to Australia from elsewhere. They are not native, and are therefore considered an introduced or invasive pest. If numbers got low, our environmental agencies would consider it a positive, not a negative, as most of these species compete with our indigenous species and livestock for limited food sources.

There are some native species that can be hunted, but mostly as part of population control, as in ensuring their numbers do not become unmanageable.

As a result, many Australian hunters find it hard to grasp the concept of conservation hunting – ie. hunting a species to increase its numbers. It almost seems like an oxymoron. How can something grow if you’re killing it off?

But conservation hunting models exist all around the world and are backed up by science.

During the Industrial Revolution, the US changed from a mainly rural population to a largely urban one. As a result, society moved from a subsistence culture to a consumer culture. Cities sprang up all over the continent and people started buying their food instead of growing or hunting their own.

This mass urbanisation not only resulted in habitat loss, it also saw the birth of market hunting (commercialisation of wild game) to satisfy the appetites of the growing population.

Wild turkey, white tail deer, bison, elk, ducks, bears and mule deer meat became a status symbol for the rich and pretty soon, their numbers had plummeted to record lows.

It was recreational hunters that came up with the best ideas on how to halt the destruction. President Theodore Roosevelt, an avid recreational hunter, established the Boone and Crockett Club, the world’s first wildlife and habitat conservation group. He was also influential in creating the first national parks, and pushing for wildlife management to be legislated.

In 1937, hunters lobbied the government asking them to implement an 11% excise tax on the sale of guns, ammunition and hunting equipment, with the money going directly back into habitat conservation and wildlife programs.

Today, the money raised from recreational hunting and fishing accounts for 60 percent of all wildlife funding in America.

While it took a little longer, the story was much the same in South Africa. As the population grew and cities began to spring up around the country, people began migrating to cities, which meant massive tracts of land had to be cleared for farmland.

Wild animals were seen as a direct threat, either through eating and damaging crops, or attacking livestock and humans. Wildlife was not protected, except on a handful of national parks.

In 1964, the government estimated that only 575,000 wild animals remained in South Africa, with many species critically endangered.

Yet it took them until the mid 1990s to come up with a solution.

That solution flew in the face of anything today’s animal activists would suggest. Rather than stopping hunting all together, the government introduced the Game Theft Act, which allowed private citizens to start game parks, and own wildlife, and shock horror, let people come from overseas to shoot them as trophies!

How could this possibly be seen as a way to save endangered animals?

In short, what they did is put a value on the life of a wild animal, and as a result, people stop treating them as a threat to their livelihood and started seeing them as a source of it. Human nature protects that which is valuable.

Today, South Africa has more than 24 million wild animals. The country still only has a small number of national parks (23) but there are more than 10,000 privately owned game parks covering 21 million hectares (or around 20 percent of South Africa’s landmass).

Species that were previously critically endangered, like the sable, black wildebeest and white rhinoceros, are now growing and coming off the endangered list. Species such as giraffe, lion and elephant, which are still threatened in other African nations, are abundant in South Africa. In fact, some of these, like the elephant, now have to be actively managed to reduce their populations to stop them impacting on the environment and other wildlife.

So back to the zebra, hunting is an important tool in creating value for zebras, which has already been proven to increase rather than decrease their populations. That’s why zebra numbers are healthy and growing in South Africa, while ironically shrinking in countries that ban trophy hunting!

Isn’t it too easy to hunt a zebra?

When people ask this question, they often assume a zebra behaves the same as a domesticated, paddock-dwelling horse, in which case hunting one would be akin to shooting fish in a barrel!

But while a zebra and a horse might both spend much of their day grazing grass, the zebra is a wild animal that is always ready to flee at the slightest provocation. That’s because zebra are prey animals. They are an important food source for both predators and scavengers. Horses were also prey animals once upon a time, but domestication has bred that flight response out of them.

One of the reasons zebra live in large herds is to minimise their risks of becoming lunch. If two heads are better than one, a whole herd of heads makes it much easier to see danger and run from it. And when they run, they do so at a speed of roughly 65km/h.

They might look like they stand out in a crowd, but zebra are not actually that easy to see. Their stripes help them to blend into trees and shrubs, while the geometric patterns of their stripes make it harder for predators to determine how many zebra there are in a herd.

So no, it is not as easy as just walking up to a zebra grazing in a paddock and pulling the trigger.

Hunting zebra involves a lot of walking, a lot of sneaking and stalking. In essence, hunters need to mimic the actions of a predator, creeping as close as they can without being spotted by one of the many eyes seeking out danger. If all that goes well for you, and you actually get within range, you then need to make sure your shot placement is good.

Anyone who has ever shot at a gun range knows that not every bullet that is fired hits its target. Accuracy depends on many things: wind, distance, trajectory, temperature, humidity, barometric pressure and the bullet itself can all have an impact on your margin of error. Add in a moving target (as in a live animal and not a static target) and the margin for error becomes even greater.

Then there’s the fact that zebra are a lot tougher than they might look. As you would have seen in episode 8, Jess shot her zebra in the lungs, and it still managed to run for more than 700 metres.

If not for the expertise of the tracker being able to pick out infinitesimal drops of blood amongst the dry grasses, they may never have found it!

Why hunt a zebra?

Now we are getting to the key question. Why would anyone actually want to hunt a zebra?

They don’t have the horns of Africa’s many antelope species nor do they have the ferocious reputations of Africa’s big game species.

When people do hunt zebra, they usually target the stallions, as they are larger and more challenging. However, in this episode, Jess deliberately chose the mare as she thought it was prettier, and had more distinctive patterns.

But isn’t that really the crux of trophy hunting? What makes a trophy? Is it the beauty of the animal? Is it the challenge? Is it bragging rights or ego?

Or is the word trophy really a misnomer?

Most people hunt for the overall experience. If they take a reminder of the hunt, it rarely has anything to do with bragging rights, and more to do with capturing a snapshot of that experience – much like someone who might purchase a souvenir while on holiday.

And despite what people may think, zebra meat is delicious. We have had the opportunity to eat zebra on many occasions, both in restaurants and purchasing it from butchers around South Africa.

When it comes to hunting zebra, the real motivations lie in conservation. By giving zebra a value, we help to ensure the locals protect and preserve them for future generations.

What is I Am Hunter?

I Am Hunter wants to change the way hunting is perceived and to change the conversation from a negative one driven by anti-hunters to a positive one led by hunters.

Our goal is to help hunters become positive role models and ambassadors for hunting, while simultaneously helping non-hunters understand why hunting is important.

You can become a supporter and help us achieve our goal and spread a positive message about hunting with the wider community.

Related content

Our other channels

Get our newsletter

Get our free monthly newsletter direct to your inbox

Listen on iTunes

Listen to our podcast on iTunes.

TV series

Watch I Am Hunter episodes on My Outdoor TV (MOTV)