Did you know that recreational hunting has done more to save critically endangered wildlife species than all other conservation activities combined?

Recently, we looked at how South Africa had used privately owned game ranches to bring many species, like the white rhinoceros and sable, back from the brink of extinction.

In this article, we’ll examine the North American Wildlife Model that has single-handedly saved iconic species like the elk, whitetail deer, wild turkey, pronghorn antelope and black bear and resulted in hundreds of millions of acres of being set aside for wildlife conservation.

Both of these conservation models revolve around recreational hunting.

In America, hunters contribute a whopping 60 percent of all wildlife conservation funds despite making up less than 5 percent of the total population.

America’s Dark Ages – 100 years of slaughter

The North American Wildlife Conservation Model is certainly one of a kind, and widely acknowledged as the most successful conservation model in the world but America has not always been a shining beacon for wildlife protection.

In fact, for over a century, they were responsible for some of the worst atrocities against wildlife ever witnessed on earth.

Take bison for instance. When America was first colonised, 30 million bison roamed the Great Plains. In order to take the land, the early settlers needed to conquer the Native Americans, and the US Army thought the best way to conquer them was to take away their most important resource – the bison.

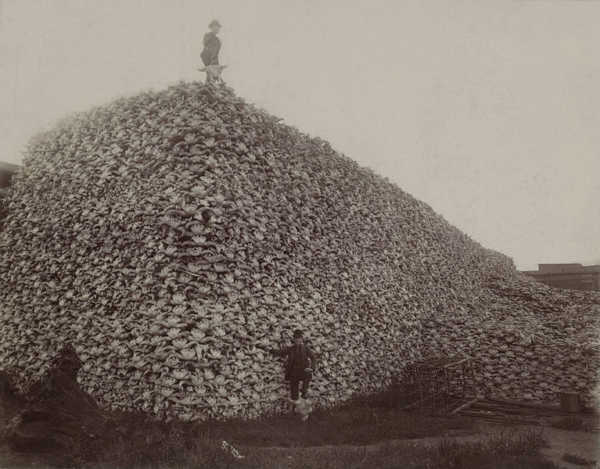

In 1830, the US Army launched an unprecedented attack on the bison, employing commercial hunters to slaughter whole herds, their bones piled sky high. By 1884, bison numbers had plummeted to just a couple of thousand.

But it wasn’t just the bison that suffered under the advance of civilisation.

As cities sprang up across the newly formed nation and the Industrial Revolution took hold, the need for food also grew. In 1820, just 5 percent of Americans lived in cities. By 1860, that number had swelled to 20 percent. Today, roughly 80 percent of Americans live in urban centres.

The growing urban population fuelled a new industry for market hunters looking to make a profit off the seemingly plentiful wild game. Bison, elk, deer, antelope, ducks, bear and turkeys soon found their way into restaurants and private homes, becoming a status symbol for the newly minted wealthy elite.

What wasn’t slaughtered for military advancement and market hunting had been displaced by the rapid expansion of agricultural land, with millions of acres of vital wetlands cleared for crops.

Bears, wolves, and mountain lions were ruthlessly hunted almost to extinction to protect livestock and pets, and to reduce the incidences of violent human/wildlife encounters.

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, America’s bountiful wildlife was in dire trouble.

Desperate times, desperate measures

Ironically it was recreational hunters (as opposed to market hunters), anglers and keen outdoorsmen that first recognised the desperate plight of America’s wildlife.

Hunters like Theodore Roosevelt and George Bird Grinnell were instrumental in rallying for changes to wildlife conservation and protection, encouraging their fellow hunters to lobby governments to implement regulations and bag limits to protect and conserve the wildlife they loved and revered.

Hunters saw that desperate times called for drastic measures. If they were going to save wildlife, they were going to have to take up the charge themselves – not wait for the government to take action.

In 1887, Roosevelt and Grinnell established the Boone and Crockett Club – the first wildlife and habitat conservation group in the world, an early influencer in the creation of several national parks and the first group to push for wildlife to be legislated. The Boone and Crocket Club were also the first environmental group to use science as a basis for conservation decisions, and to establish the principles of ethical and sustainable fair chase hunting.

Hunters also saw the need for a significant and sustainable source of funding for wildlife management. In 1937, sportsmen successfully lobbied Congress to pass the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act, which put an 11 percent excise tax on the sale of all sporting arms and ammunition. This was followed in 1950 by the Dingell-Johnson Act, which placed a similar tax on fishing equipment.

Today, this self-imposed tax generates upwards of $1,000,000,000 (B) every year, which together with the funds raised through state license and tag sales constitutes over 60 percent of all funding for wildlife in North America – funds that would be lost if anti-hunting organisations got their way and banned hunting. This money benefits all wildlife, not just huntable wildlife.

Over the last hundred years, hunters and anglers have created a steady stream of private conservation groups, such as Ducks Unlimited (which has restored more than 13.8 million acres of wetlands), National Wild Turkey Federation (which has been instrumental in seeing turkey numbers grow to around 7 million, up from just 200,000 in 1940), and Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation (which has conserved and enhanced more than 7.1 million acres of vital habitat for elk and other wildlife). These organisations, and others like them, have raised vital funds through their membership fees and restored huge tracts of land for the protection and conservation of American wildlife.

Successful conservation

The result of following this method of conservation has been unprecedented success in repopulating wildlife populations over the last century.

- Elk herds have risen 2339 percent, from 41,000 to more than 1 million

- Wild turkey flocks have grown 2900 percent, from around 200,000 to more than 6 million birds

- Whitetail deer have grown 4900 percent, from 500,000 to 25 million deer

- Black bear were almost extinct in the early 1900s. There are now more than 300,00 – that’s a growth rate of 29,900 percent!

- Pronghorn antelope have grown 8233 percent, from 12,000 to more than 1 million

- And bison herds have grown a whopping 49,900 percent, from a low of 1000 bison to more than 500,000 today. While that is still well short of the massive number of bison that once roamed North America, it is an impressive success rate nonetheless.

Core principles of the North American wildlife model

Wildlife as a public trust resource

Unlike Australia where no one really owns wildlife, in North America wildlife (both fish and game) is held in public trust by the state and federal governments. Individuals may own the land that wildlife resides on but they do not own the wildlife. Instead, it is owned by all citizens.

Elimination of markets for game

After the dark days of commercialised market hunting that almost wiped out entire species, commercial hunting and the sale of wildlife is now prohibited in North America. This ensures wildlife populations do not become economic markets (thus privatising a public resource) and remain sustainable for future generations.

Allocation of wildlife by law

Under North American law, wildlife is recognised as a public resource, with laws regulating access to wildlife include the 1940 Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, Endangered Species Preservation Act, Fur Seal Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, and the 1973 Endangered Species Act.

Legitimate use

Under the North American Model, it is considered unethical and unlawful to kill fish or game without making reasonable effort to retrieve and use the resource. This broadly means that wildlife can only be killed for a legitimate purpose such as food, fur, self-defence, and the protection of property, including livestock and crops.

Wildlife is considered an international resource

The North American wildlife model recognises that wildlife does not just exist within fixed political boundaries and can cross borders – ie. migratory birds, fish etc. With this in mind, effective management must be done internationally, through treaties and the cooperation of management agencies.

Science-based decision making processes

The North American Model puts an important emphasis on science as a basis for informed management and decision-making processes, drawing on the expertise of wildlife biologists, environmental scientists and other professionals to inform decisions, determine population limits and release the appropriate number of tags as a result of those studies.

The Democracy of hunting

In many countries, hunting is restricted both by way of access to land, and the right to own and use firearms. Theodore Roosevelt believed that all citizens should have equal access and opportunity to hunt, as he believed it provided many societal benefits and set the people apart as free citizens not serfs. For this reason, he believed the right to hunt was an important hallmark of democracy.

Applying this model to Australia

In Australia, wildlife doesn’t really belong to anyone. While there are Federal and State laws around the treatment of most animals, and limited budgets to manage the environment, the absence of ownership creates a vacuum whereby nobody really takes responsibility for wildlife, as a collective.

As a result, very few of the core principles of the North American model currently apply here. However, there are potentially ways that we could sensibly apply these principles to our wildlife conservation efforts. These include:

- the government enacting laws to protect wildlife and recognise it as a valuable resource for all Australians, rather than just introduced or feral pests

- managing wildlife using quotas and hunting tags based on scientific data for specific areas

- introducing carefully regulated hunting quotas to manage native wildlife species

- introducing an excise tax on hunting and fishing supplies to be used to directly support wildlife conservation and open up land for hunting

- creating private conservation trusts, such as Ducks Unlimited and the Boone and Crockett Club with the specific aim of holding land in trust for hunting

- recognising hunting as a valuable and much needed activity in the management of wildlife

What other things do you think Australia could learn from our North American counterparts on wildlife conservation?

Sources used for this article

The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation

Hunters’ Contribution to US Wildlife Conservation

Conservation Strategies for Bighorn Sheep

What is the Dingell-Johnson Act

What is I Am Hunter?

I Am Hunter wants to change the way hunting is perceived and to change the conversation from a negative one driven by anti-hunters to a positive one led by hunters.

Our goal is to help hunters become positive role models and ambassadors for hunting, while simultaneously helping non-hunters understand why hunting is important.

You can become a supporter and help us achieve our goal and spread a positive message about hunting with the wider community.

Related content

Our other channels

Get our newsletter

Get our free monthly newsletter direct to your inbox

Listen on iTunes

Listen to our podcast on iTunes.

TV series

Watch I Am Hunter episodes on My Outdoor TV (MOTV)

10 thoughts on “What can Australia learn from the North American wildlife model?”